The 90 Hour Workweek

What would you have to give up to work longer hours? You could spend less time staring at your spouse. But data suggests that your spouse isn't exactly waiting around to be stared at.

The Cosmic Ulcer

My wife and I recently had a... discussion. I don't exactly remember what it was about. But it was something to do with home improvement... something like doorknobs or curtain rods. Whatever it may have been about, at the core of it was an ideological difference. My wife believes that even the smallest inconvenience should be immediately addressed - immediately being the operative word. I, on the other hand, think that most small inconveniences can wait. In fact, I firmly believe that just because something is doable doesn't mean it ought to be done. There's an infinite number of doable things. Undoable things, on the other hand, are very few. There's nothing inherently special about most things that are considered doable.

Before I realize it, I'm actually saying all of this out loud with a lot of sincerity. She initially finds it amusing: I can't be serious! How does something as trivial as a broken doorknob push me into delivering a deep metaphysical thesis? As I ramble on, her amusement becomes frustration. She reminds me that the whole issue is a lot simpler than I'm making it - it's all about a few stupid doorknobs. Why can't I just fix them today? I don't know what to say.

The answer is actually pretty straightforward - interruptions have a cost. And for programmers (I've been working from home for the last seven years), interruptions are unaffordable. It takes programmers 10-15 minutes to resume work in earnest after being interrupted1. My wife and my cook both know that even the smallest, most straightforward question will garner an unfocused, glassy-eyed stare, accompanied by a "huh...?!" So when I can't explain why I don't particularly care about what I eat or wear - it's the same basic principle. Decisions, no matter how trivial, have a cost.

But there's no way I can say this to someone, let alone my significant other, without sounding like a pompous, self-important jerk.

So the path of least resistance is to just fix the doorknobs. But close on the doorknobs' heels are doorstoppers the dog chewed off, the sofa cushions with only the smallest visible tears, the printer cartridge refills and the endless stream of tiny decisions...

... but how about little faults, little pains, little worries. The cosmic ulcer comes not from great concerns but from little irritations. And great things can kill a man, but if they do not, he is stronger and better for them. Man is destroyed by the duck nibblings of nagging, small bills, telephones, athlete's foot, ragweed, common cold, boredom. All of these are the negatives, the tiny frustrations and no one is stronger for them.

- John Steinbeck, Journal of a Novel: The East of Eden Letters

I shared this quote with my wife once. She said, "It's almost as if you dictated this to Steinbeck." It was easily the most flattering thing anyone had ever said to me. But as I visibly gloated, she added that she didn't mean it as a compliment.

Over time, I’ve come to think that while Steinbeck meant to write about the gender-neutral “man”, but it landed squarely in the male sense. There exists an opposite perspective of “the negatives, the tiny frustrations” - one that Kanchan Balani calls “not errands, but love letters to the world.”

Then we’d tackle whatever needed fixing that week: the mixer grinder’s stubborn motor, new batteries for a dying watch, shoes with broken straps. Finally came my favourite part: long walks in the park nearby, followed by sugarcane juice that painted green moustaches on our faces as we giggled in the golden light. In that park, peacocks would strut between the trees, and I’d always return home clutching a perfect fallen feather – my weekly treasure, proof of magic found.

- Kanchan Balani, It's the Small Things | Everyday Errands

For me, the cosmic ulcer didn’t always exist. A decade ago, life was just sorted. Both of us had a fairly predictable job, and a fixed routine. We would see each other only at dinner and on weekends. Even the time spent on leisure was fixed - reading on the train, Netflix during dinner and video games and socializing over the weekends. Doorknobs were strictly the landlords' headache. It was all very comfortable. It never occurred to me that the routine could be suboptimal. No thoughts of optimization or efficiency crossed my mind.

And then something broke. I didn't quite know what.

I took a new job. It was a dream job - the kind that you think you'll spend the rest of your life at. There was only a small team in Delhi and no office. So I worked from home. For the first time in life, I had more time than I knew what to do with. Initially all the extra time felt like a great luxury. Like a dutiful worker, most of the leftover time went into doing extra work. I quickly emerged as the new guy who gave more than 100%. I soon realized that being that guy has diminishing marginal utility. But by then I already had a reputation - and upholding it meant that I had to squeeze every last droplet of time and siphon it into work. This, in turn, meant that there was less time for everything else - especially leisure and relationships. And, naturally, all concerned parties grew irritable, bitter and unhappy - in that order. This was classic burnout, but, in my infinite hubris, I refused to admit it even to myself. Finally, as a self-respecting hacker, instead of solving the root cause of burnout, I avoided it altogether with productivity hacks.

What had broken was Time - my idea of it and how I used it.

Personal productivity wasn't yet the widely influential global enterprise it is today. Sadly, the people wielding that influence today seem to suffer from the Kardashian effect - they seem to be only productive at creating content about productivity2. My journal entries from that period (journalling, too, was something that productivity gurus recommended - I didn't start enjoying it until much later) are full of whining about how I couldn't get enough done. Ultimately I realized that my ideal day was getting more and more ridiculous and impractical. The day would never come when I get up early, do enough exercise, crack off a major work problem before lunch, read a book in the late afternoon, work on a side project in the evening, take a leisurely walk in the park with the dog, and top off the day with a deep conversation over dinner. When I look back, I see that that was the last time I whined about not getting enough done. So, eventually, many books, articles, podcasts and videos later, I gave up on productivity hacks3.

This was the second time Time broke, coinciding with the COVID-19 lockdown. All hacks broke. Routine broke. Habits, albeit with a lot of effort, broke. The only "hack" that remained was to work with depth and focus at a slow and steady pace. Cal Newport would eventually call this slow productivity. It worked well enough for me to do some of my best work.

After all that breakage, what remains with me is a small set of ideas - don't multitask, deal with interruptions the best you can, sleep well, etc. I no longer claim or aim to be the master of my time. It's not even like I'm cured of the cosmic ulcer - far from it. I just care less now.

Every now and then I see success stories of slow productivity - small doses of vindication for my rediscovered approach. A friend heard my rant about doorknobs. He could not have been more sympathetic. He admitted that non-programmers rarely understand flow and uninterrupted immersion, and how, in social conversation it is difficult to defend not fixing a doorknob. He then shared with me a Quanta profile of June Huh. "Somewhere here there's a story of a Fields medalist stapling together a makeshift blanket...", he said. June Huh is a late blooming mathematician who dropped out of high school to write poetry, then got enrolled in a math course, took six years to graduate and finally went on to win the Fields medal. He is described as extremely slow and methodical. He hacked together a blanket from scrap cloth because going to buy a proper blanket was too mentally exhausting. I somehow just get that.

There's also the story of the great Richard Hamming. In his classic lecture You and Your Research, he advocates exceptional ambition, attitude and passion. His idea of knowledge and productivity being like compound interest has stayed with me since my college days.

Both Hamming and Huh are poster boys of deep work and slow productivity. But there's also something else that's common between Huh and Hamming - both their wives had to put up with their shenanigans. Huh admits that his wife was disappointed at the lack of balance in his life. Hamming, too, admits that he "sort of neglected" his wife sometimes, "You have to neglect things if you intend to get what you want done."4

It's infuriating how, even with the best of intentions on your part, there's always someone else paying the price of your productivity - a parent, a spouse, a child or a pet.

So now imagine my indignation when a captain of industry tells me that I ought to be working 90 hours a week, through weekends, and that I've been staring at my spouse for too long.

The War on Time

N R Narayana Murthy wants people to work 70 hours a week. And frankly, that doesn't sound too bad. But S N Subrahmanyan dials it up to 90 hours a week. Bhavish Aggarwal claims to work 140 hours a week. He believes that weekends and work-life balance don't apply to Indians because they are a western concept. He may be right, but only a little homework would have revealed that the concept of leisure isn't foreign at all. It is advocated in something quintessentially Indian - the Constitution.

The State shall endeavour to secure, by suitable legislation or economic organisation or in any other way, to all workers, agricultural, industrial or otherwise, work, a living wage, conditions of work ensuring a decent standard of life and full enjoyment of leisure and social and cultural opportunities...

- Article 43, Directive Principles of State Policy

Now, credit where it is due, building and running an industrial empire must come with a deep understanding of how people do their best work. But when exhortations to work longer hours are accompanied by news of stress-induced diseases, deaths and even suicides in the workplace - it's clear that this fanatical quest for workplace productivity is not just misguided, but also tone-deaf. It is also, as we shall see, inevitably sexist.

How the Salaried and Skilled India Works

Between January and December of 2024, the National Statistical Office conducted the second national Time Use Survey (TUS) in India (The first was conducted in 2019, before the pandemic). It offers precisely the kind of data that helps us address the question of how feasible long work-hours are, and who they affect the most. As I wrote the following section, the central guiding question in my analysis was,

If people had to work 90 hours a week, what would they have to give up?

The 2024 TUS covers the entire country apart from some inaccessible parts of Andaman & Nicobar, and is administered over the whole year to account for seasonal variations. For each respondent, it records the time spent on everything in the last 24 hours in 30 minute intervals. As such, it presents an exceptionally detailed view of how people spend their time. The survey data is rich beyond an analyst's dreams... after losing myself for weeks in the labyrinth of the various possibilities of filtering the data and designing sample cohorts, I've settled down on a ruthlessly simplified but still rigorous approach to the data.

For one, I will be writing about that subset of the population which is most likely to be at the receiving end of productivity-shaming: salaried white-collar workers. The TUS helpfully includes a field which records whether each respondent was involved in an economic activity, and if so, whether they were self-employed or salaried. In addition, the survey also records the industrial classification of the relevant economic activity. With a combination of these two and the typical working age (15-60 years), I created filters which indicate whether someone can be asked to work for 90 hours a week with a straight face5.

Even this modestly-sized sample of the white-collar workforce is still quite fertile. Fortunately, there's no demographic which is excluded from it. People of all religions, castes, educational backgrounds, ages and genders find decent representations in the sample. Of these, some are more indicative (meaning, correlated with) the use of time in specific activities than others, as we shall see. The effects of some of these demographic variables are subtle, they show up only in very nuanced conditions and with smaller effects. Others jump right off the computer screen. The biggest example of the latter is gender. The fact that time use is gendered wouldn't surprise anyone, but the extent of the effect of gender is staggering. Gender beats all other attributes of the respondent by far, and there's no way you can manipulate the data which makes this effect disappear6.

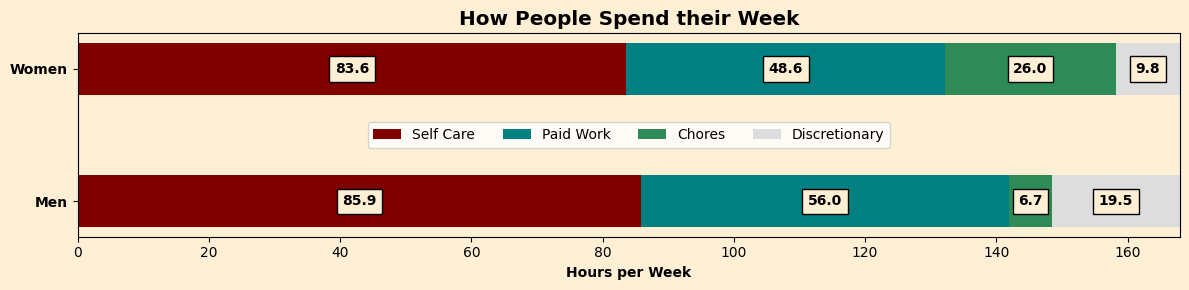

If we simply look at the average time men and women spend on different types of activities and adjust it for the week, the picture doesn't look bad at all. Both men and women spend about 85 hours a week on self-care and maintenance. This includes activities like sleep, personal care, hygiene and non-social eating and drinking. Men work nearly 56 hours a week, and women work 48.6 hours a week. This translates into women working only an hour less than men every day. If you've wondered if your female colleagues seem to consistently leave the office earlier, here is statistical proof.

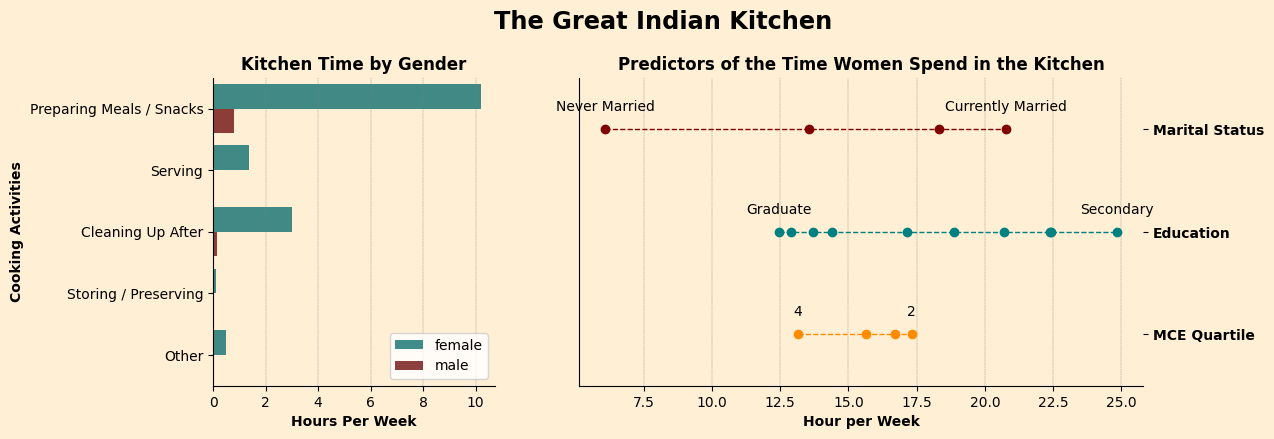

It is in the next category of activities that things get interesting. Women spend four times as much time on chores (they're designated as "unpaid domestic services for household and family members" under ICATUS) than men7. Activities under this category involve working in the kitchen, doing the laundry and other miscellaneous household management. In our quest for the 90 hour workweek, it's pointless to look at anything but the largest component of chores, and that is the kitchen.

Here, too, the magnitude is more surprising than the direction. We'd expect that men spend much less time in the kitchen than women overall in the country - and we'd be right. But to see that happen even in a small, presumably emancipated section of the population is shocking. Even among the salaried class with skilled jobs, men barely spend an hour cooking. Moreover, cooking is only a part of kitchen work - there are also the allied activities of serving food and cleaning up after, where men are insultingly absent. This reminds me of a scene from the Malayalam movie The Great Indian Kitchen (which was also captured well in its Hindi remake) where an overbearing relative announces that he's going to make dinner, that the women can rest, but ends up leaving the kitchen in a mess.

Other factors associated with kitchen time - like marital status, education and household wealth - also influence it in expected ways. But the relationship between them and time spent in the kitchen isn't just monotonic - it is extreme. The women who come from the wealthiest quartile spend nearly three hours less in the kitchen than those from the second wealthiest quartile. Women with graduate degrees spend nearly 12.5 hours per week in the kitchen, and as education drops to the higher secondary level, the time spent almost doubles. Going from being single to being married increases the time spent in the kitchen by a whopping ten hours per week.

The time spent in chores (particularly in the kitchen and otherwise in cleaning and laundry) is inversely correlated to the presence of labour-saving devices and methods in the household. This is not surprising, but it _is_ statistically significant. What is surprising is that these devices don't have as large an effect as we'd expect. Come to think of it, washing machines, refrigerators, microwave ovens and vacuum cleaners are technologies that are old enough to have revolutionized chores. They are generally reasonably priced, too. Given that we're talking about a relatively better off section of the population - why don't we see a larger effect? I don't have a clear answer, but I did get a very interesting perspective from Krish Ashok, in one of his most interesting podcast moments:

“...optimizing cooking time with appliances is a progression. My grandfather didn't like rice cooked in a pressure cooker. A generation before they didn't like stoves, and preferred wood fires. Nowadays they don't like microwaves and air fryers and say that refrigerated food loses nutrition. Whenever there's a new tool for improving kitchen productivity, there will be an entire generation of men and women resisting it...”

Anyhow, for the sake of argument, let us allow ourselves, for the time being, to dream of a world where both men and women spend significantly less time on chores. Let's say, optimistically, that both genders spend no more than an hour a day on chores, and pump all the remaining time into work. Even in this ridiculous world, women's work time would grow only to 67 hours a week. The situation for men would not change since they already work less than an hour per day on chores. To hit the 90 hour / week target, there's still a large deficit - 22 hours for women and 34 hours for men. At this point, work has no choice but to eat into sleep and leisure.

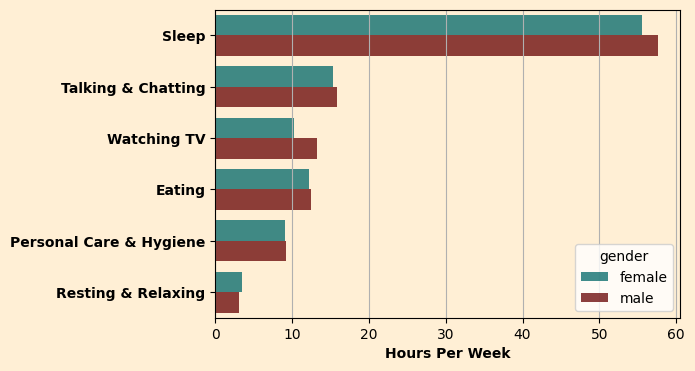

This is probably the only chart in my entire analysis which looks gender balanced. In fact the only small imbalance I see is that men watch TV for a couple of hours longer than women (presumably when their wives are in the kitchen). Otherwise both genders spend comparable amounts of time sleeping, talking, eating and otherwise chilling. It must be noted, however, that I've wrought an anomaly here by cherrypicking a specific cohort - otherwise, in general, time spent on leisure and self-care is also heavily gendered. For instance, women take 2.3 times as long as men to use the toilet8 - there's no way that personal care and hygiene costs both genders the same amount of time across the country. Even socialization and relaxing can mean different things to both genders. In her book Whole Numbers and Half Truths, Rukmini S writes some very interesting examples of how leisure means different things to different sets of Indians, particularly to men and women. Even something as innocuous as commandeering the TV remote can affect how women feel about their freedom of leisure.

But as far as this cohort of salaried white-collar workers is concerned, this chart tells us that there's a lot of productivity still to be squeezed out. For example, both men and women could do with an hour less of sleep everyday. For one, seven hours a night is by no means cruelly short. For another, every productivity guru worth their salt will tell you that it's the quality of sleep that matters more than the duration. That's seven hours added to the respective deficits right there!

When it comes to talking, chatting and texting, 15 hours a week looks downright excessive. All 10-12 hours of watching TV could be cut down. There's certainly some creative incentive that managers can come up with to get people to cancel their Netflix subscriptions and delete their Instagram accounts. In fact I'll go so far as to say that even some personal care and hygiene can be sacrificed. Ask Bhavish Aggarwal - if he can work 20 hours a day and still afford to look somewhat well groomed, what’s your excuse? Of course, haters could ask why working 20 hours a day isn't enough for him to make decent scooters. If we're going to make reasonable arguments like time spent on work is no guarantee of quality, this whole post is moot.

A colleague of mine once took a picture of a couple of his teammates sitting with their laptops open in the back of an autorickshaw, in the middle of a busy Hyderabad street. The marketing team picked it up and used it in a social media campaign with hashtags like #hustle, #dedication, #productivity, etc. All I could think of was what a potential client might think about the quality of our work if we were so busy hustling.

Another colleague once posted a picture of himself sitting on his desk, hunched up over his laptop with the caption, "burning the midnight oil after everyone has gone home." Someone asked him who took the picture if everyone had gone home. He didn't reply.

I don't honestly think that people actually confuse time with productivity. Nobody is that stupid. But knowledge workers aren't turning out widgets on an assembly line. Time spent is perhaps the only lead metric of productivity we have.

The single most enjoyable thing about being a programmer is the obsessive pursuit of a complex problem. Every good programmer has a lot of experience with spending hours and days holed up in a room with an unhealthy disregard for food, sleep and general well-being. It is the cost of what we do. It is why we're able to take any pride in our craft. It's the rite of passage of every true hacker. And they suffer from it, too. I recently ran into some old friends at a conference. A decade ago, we could talk of nothing but the hustle. This time we only complained about our backs, our necks and our cholesterol levels. So, I understand only too well the appeal of working longer hours. It's not that I'd never sell long hours to my younger colleagues.

But I know bullshit when I see it. Long hours were never sold to me on a platter of nation building. It took me a while, but I recognized precisely what enables me to work long hours, and I acknowledged my privilege. I can think of no better acknowledgement than this quote from Stephen King:

The combination of a healthy body and a stable relationship with a self-reliant woman who takes zero shit from me or anyone else has made the continuity of my working life possible.

- Stephen King, On Writing

But when people ask you to work ridiculously long hours, healthy bodies and stable relationships are exactly the kinds of things they want you to give up.

It better be worth it.

Acknowledgements: Special thanks are due to Prof Ashwini Deshpande for helping me navigate the Time Use Survey microdata, and to Sameera Khan for her perspectives on gender equality in the workplace.

Perhaps with a few exceptions like Cal Newport - who has a very real (and a very difficult) job.

Oliver Burkeman's book 4000 Weeks: Time Management for Mortals might have had something to do with this.

The Stripe Press edition of Hamming's The Art of Doing Science and Engineering, which includes You and Your Research, has inexplicably and unnecessarily elected to censor what Hamming said about his wife.

In her book Invisible Women, Caroline Criado Perez has an entire chapter on the disproportionate share of women's unpaid care and household work, and what it means for the global economy.

Perez also points out that the term "working woman" is a tautology. "There is no such thing as a woman who doesn't work. There's only a woman who isn't paid for her work."

Banks, Taunya Lovell (1991), 'Toilets as a Feminist Issue: A True Story', Berkley Women's Law Journal

Well said! I will keep reading your posts as long as they start with "My wife and I had a.. discussion". It was funny and relatable.

Love your writing :)

Is the door knob fixed though?